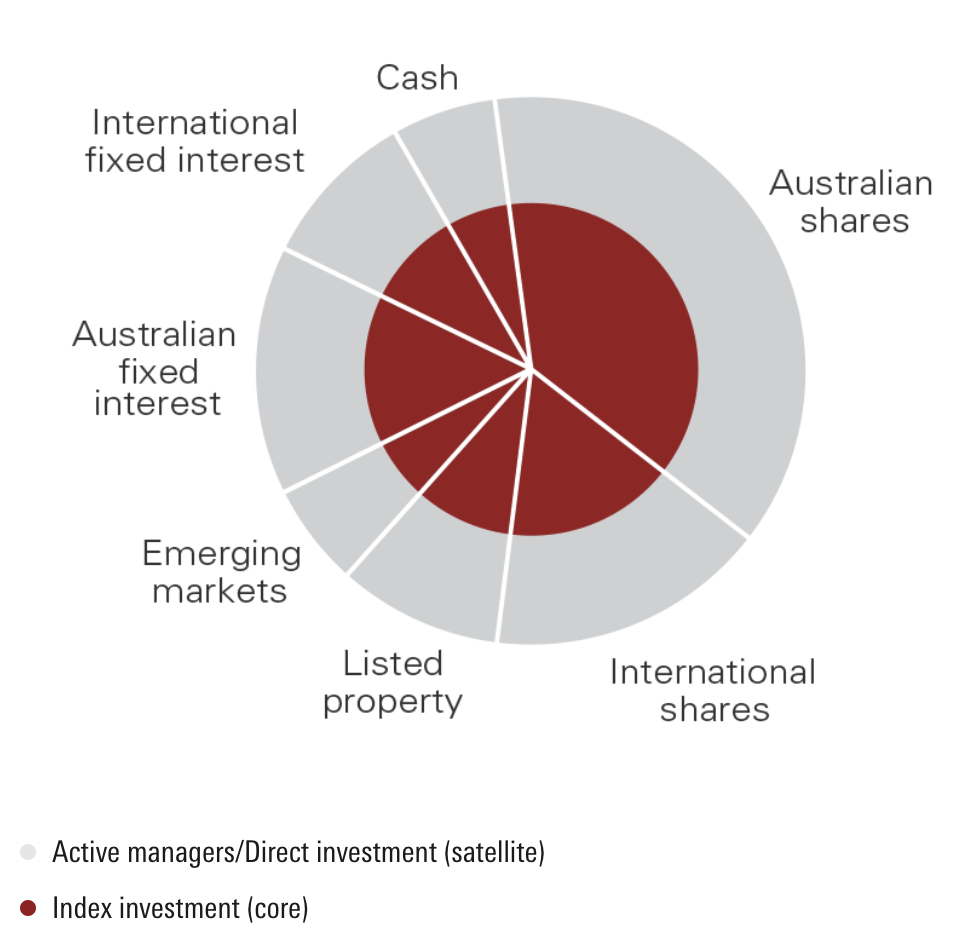

I like having an occasional tipple on individual shares, but the bulk of my portfolio is in ETFs. Turns out this is a fairly common method of investing known as the ‘core-satellite approach’ – it’s even got its own Wikipedia page.

But I might be getting ahead of myself a little. For those that don’t know, ETFs are Exchange Traded Funds, also commonly known as ‘index funds’ (though the two are actually slightly different things). The name may sound intimidating, but the concept is actually incredibly simple.

Imagine that, when you buy a share in an ETF, you’re not buying just a single share, but rather a bundle or container of other shares. For example, one very popular ETF listed on the ASX is VAS, which stands for the ‘Vanguard Australian Shares Index ETF’. VAS holds the largest 300 companies listed on the ASX (known as the ‘ASX300’) pro-rated to their size, which as we discovered from my ‘How big is the ASX‘ article, accounts for 91% of its total market cap.

In other words, when you buy a share in VAS, you are not really just investing in a single share, but rather an entire index – in this case, the ASX300.

ETFs are popular because, although the performance of individual stocks can be volatile, entire indexes tend to perform fairly consistently – especially over longer periods of time. For example, the Dow Jones, which is an index that comprises the 30 largest US companies, has averaged a 7.4% annual return over the last ~130 years:

With an ETF, you are typically spreading your risk over dozens to hundreds of companies, so if any one company fails or even just underperforms, your downside is limited.

ETFs also frequently rebalance, which is just a fancy way of saying that as individual companies increase or decrease in value, the ETF will buy or sell them as necessary to keep accurately tracking its index. So to go back to VAS as an example – if Company A’s value decreases enough that it falls out of the ASX300 and company B’s value increases enough that it enters the ASX300, VAS would sell its shares in Company A and buy shares in Company B.

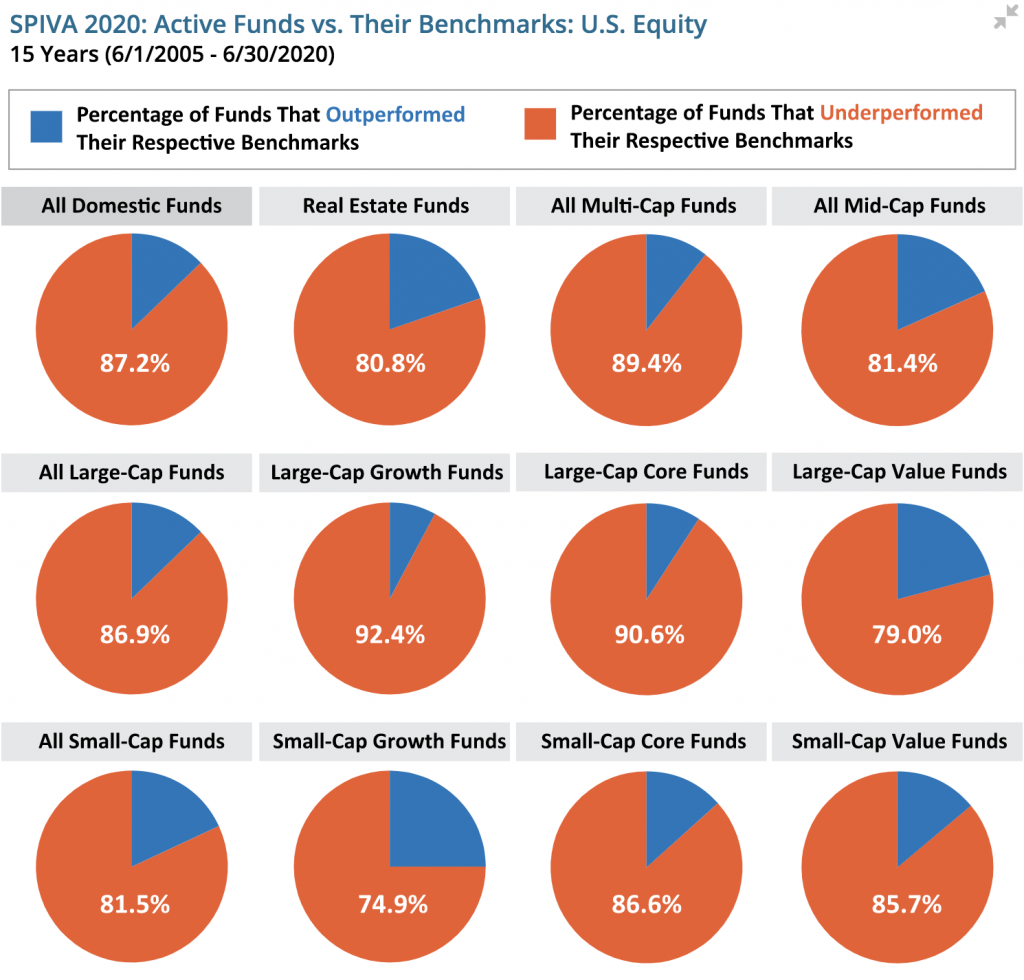

Not only are ETFs much less risky than investing in individual shares, they also tend to outperform managed funds after accounting for fees:

As the chart above shows, most of the ‘professionals’, i.e. active fund managers, aren’t able to outperform the index over extended periods of time.

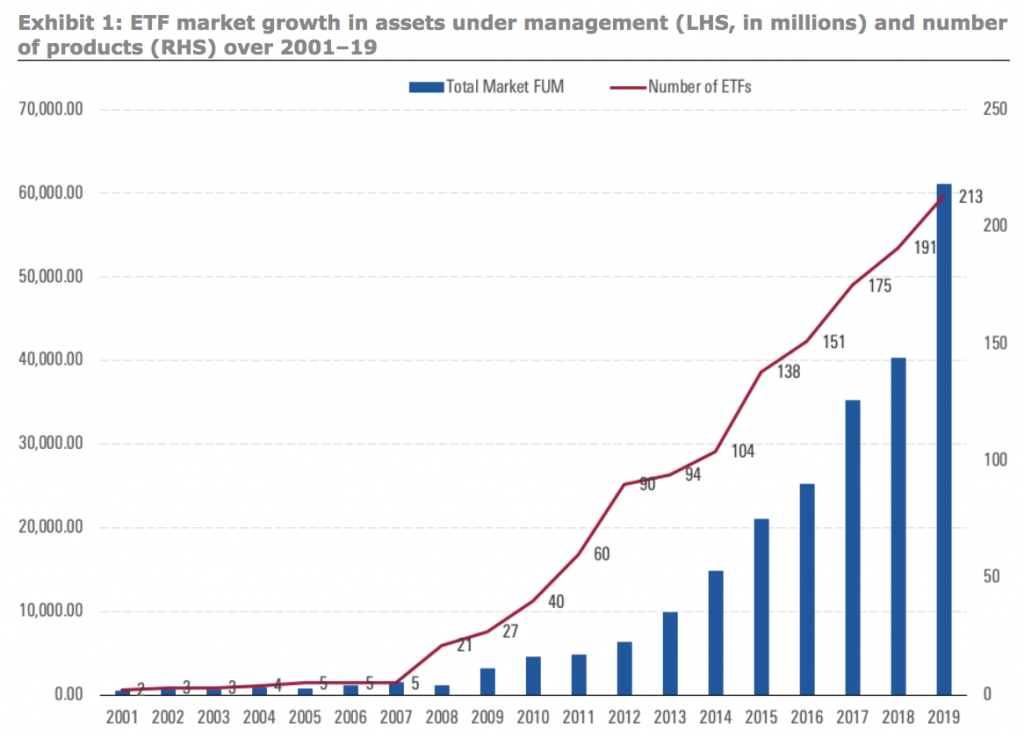

The set and forget approach, low fees, and relatively high performance of ETFs have led to an explosion in so called ‘passive investing’ over the last couple of decades, as this chart from Morningstar shows:

The blue bars show total funds under management, which rose 20-fold in the last 20 years, from 3 billion AUD to over 60 billion AUD. The even bigger increase, however, has been in the number of ETFs available on the ASX, which increased 100-f0ld over a similar period, from just 2 in 2001 to over 200 in 2019.

Ironically, this has led to a paradox of choice with ETFs. Now, instead of painstakingly agonising over which shares you should buy, you can painstakingly agonise over which mix of ETFs you should buy.

From humble beginnings and fairly vanilla offerings like the aforementioned VAS that tracks the ASX300, you can now buy ASX listed ETFs for all sorts of things, like HACK (which ‘provides simple and transparent exposure to the leading companies in the global cybersecurity sector’), ROBO (‘designed to measure the performance of robotics-related and/or automation-related companies’), and BBOZ (which ‘aims to help investors profit from, or protect against, a declining Australian share market’).

Below is a racing bar chart showing the growth of $1000 invested into a selection of 11 different ASX listed ETFs from November 2017 until November 2020 (excluding inflation and dividends). In addition to VAS, HACK, BBOZ, and ROBO, the other 9 are:

- VDHG ‘provides invests mainly into growth assets, and is designed for investors with a high tolerance for risk who are seeking long-term capital growth.’

- VGS ‘provides exposure to approximately 1,500 large-cap and mid-cap companies listed on the exchanges of the world’s major economies excluding Australia.’

- VGE ‘provides exposure to approximately 22 emerging market countries across Asia, Latin America, Europe, Africa and the Middle East.’

- MOAT ‘gives investors exposure to a diversified portfolio of attractively priced US companies with sustainable competitive advantages according to Morningstar’s equity research team.’

- TECH ‘comprises of 25 to 50 global technology companies across areas such as software, semi-conductors, data processing, computer equipment and databases.’

- VAE ‘provides low-cost exposure to securities listed in Asia excluding Japan, Australia and New Zealand.’

- DRUG ‘provides simple, cost-effective and transparent exposure to the largest companies in the global healthcare sector.’

- PMGOLD ‘is a right to gold created by The Perth Mint, which gives investors the ability to purchase Government-backed gold via the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX).’

What can we learn from the above chart? Primarily that there are now so many ETFs tracking so many different things that choosing between them isn’t all that different from choosing between individual shares, which – as we’ve already established – isn’t all that much different from gambling, even if you’re a ‘professional investor’.

Nothing in this post should be construed as financial advice, but speaking personally, I’ll be treating a lot of these newer, more exotic ETFs as if they were single shares and weighting them in my core-satellite approach accordingly. The O.G. ETFs, i.e. the ones that have the longest track records, are based around a large index (or series of indexes) like the ASX, DJIA, NASDAQ, and so on.

ETFs that attempt to track a specific industry (like ROBO) or have a strong albeit indirect active manager component (like MOAT) are very enticing and have certainly had a good run over the last 3 years as the chart above shows, but in a sense, they’re antithetical to what made ETFs so popular to begin with: a passive set and forget approach with low fees and relatively diversified risk.

In short, buying ETFs and ‘taking a punt’ are no longer necessarily mutually exclusive.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help me out, there are a few things you can do.

- I just created a Twitter account (I know, I know – bit late to the party). I promise to only post interesting things! Follow me here: https://twitter.com/LeaneJonathan

- If you have a spare couple of bucks, please consider joining my Patreon. As I said, I’d love to do this as a full time job, but at the moment I’d even settle for breaking even! I’ve set my Patreon up here: https://www.patreon.com/datamentary

- You could subscribe to my Youtube channel here: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCiqE7AFojsc6U7fqmPt2Vdg

Youtube won’t let me monetise until I hit 2000 subscribers, so there’s still a looong way to go. - You could upvote this post on Reddit, share it on FB, etc… Really, any publicity I can get at this point would be a big help.

- And finally, if you have any requests for future topics or would like to collaborate on something, please leave a comment here and I’ll get in touch.